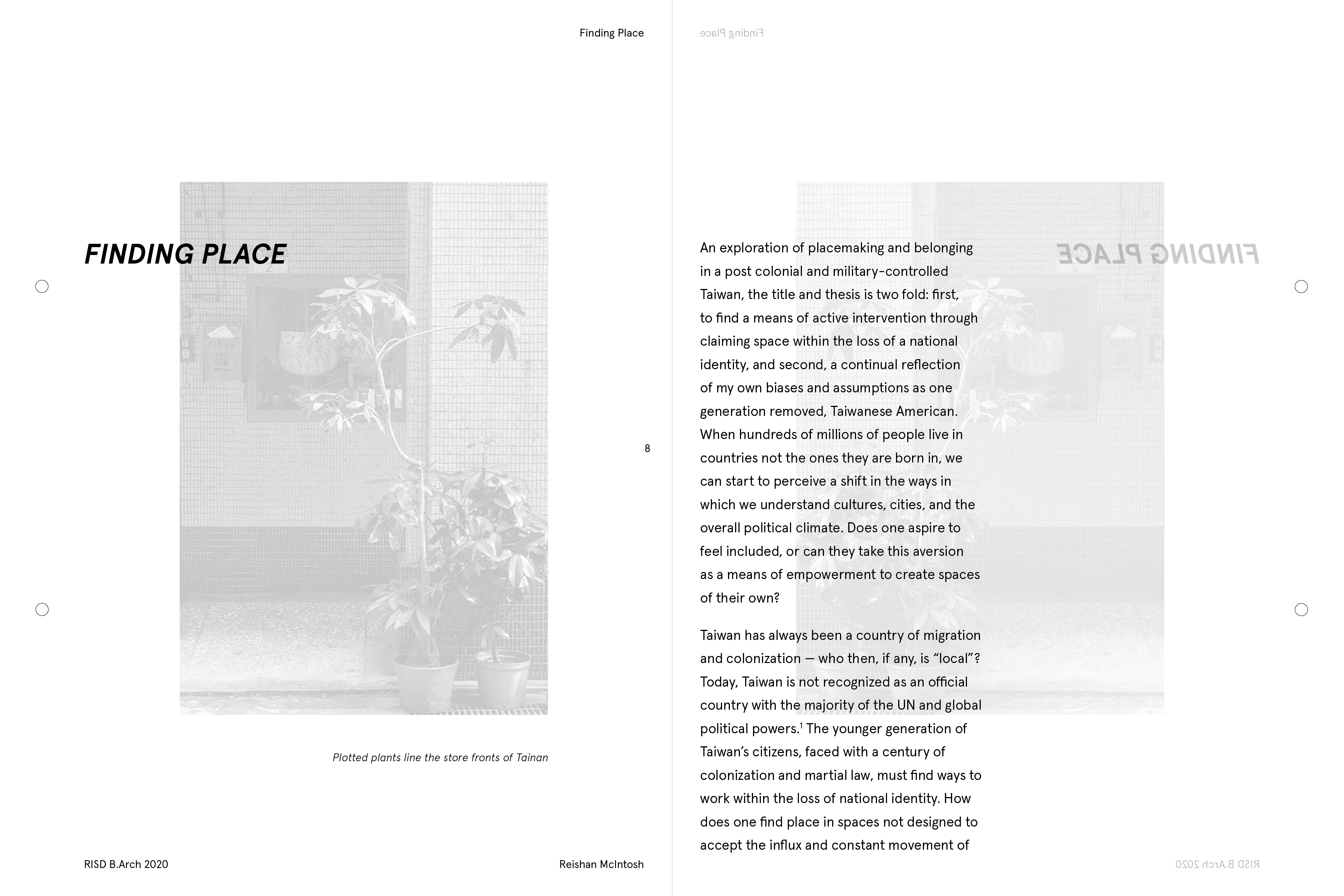

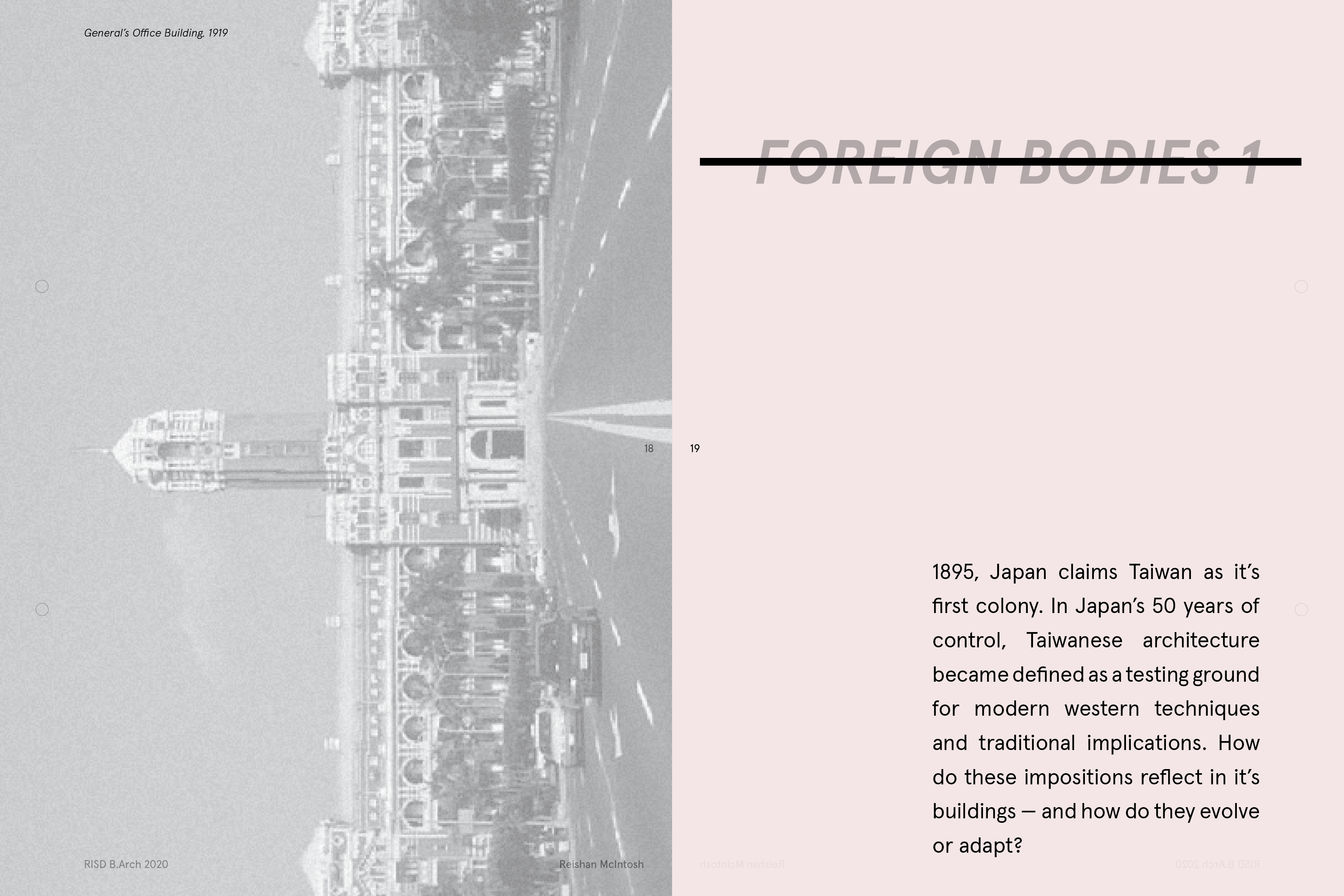

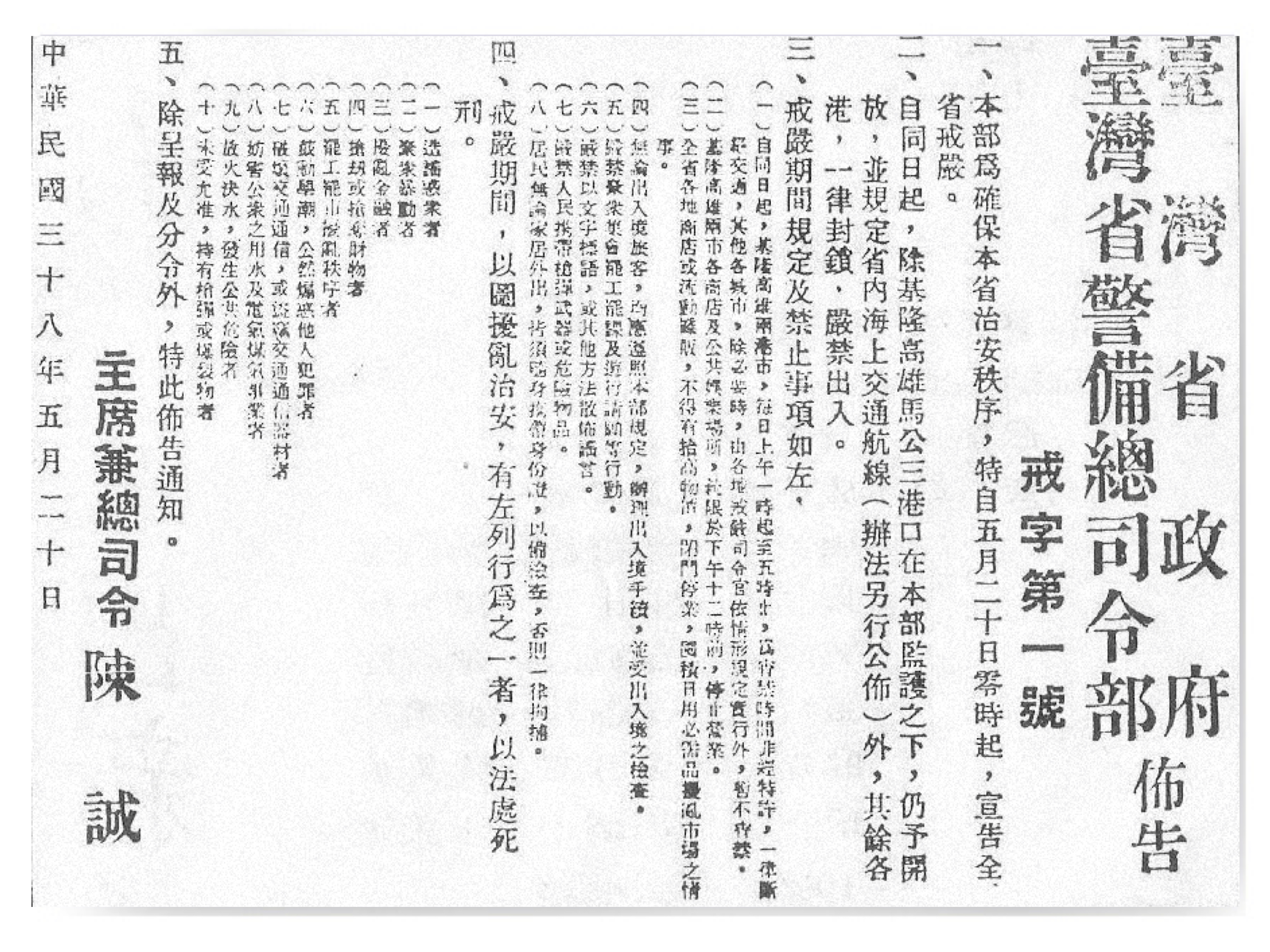

A country can be defined by its turbulent history: Taiwan has dealt with 50 years of Japanese colonialism, immediately followed by 37 years of martial law. During those 87 years, architecture became a tool to flaunt modern building technologies and to assert cultural dominance. Consequently, one would assume the violent imposition of strict and ordered hierarchy reflected in the buildings. Yet, while we see hierarchy in the macro, we also find the opposite in the micro. Taiwan’s architecture is shaped as much by its colonial and martial past as it is by the people who navigated—and continue to navigate—its spaces. As the Taiwanese adapted and lived within the imposed materials and architectural elements, a new in-between space was created by eroding the boundaries between public and private, monumental and adhoc, inside and outside.

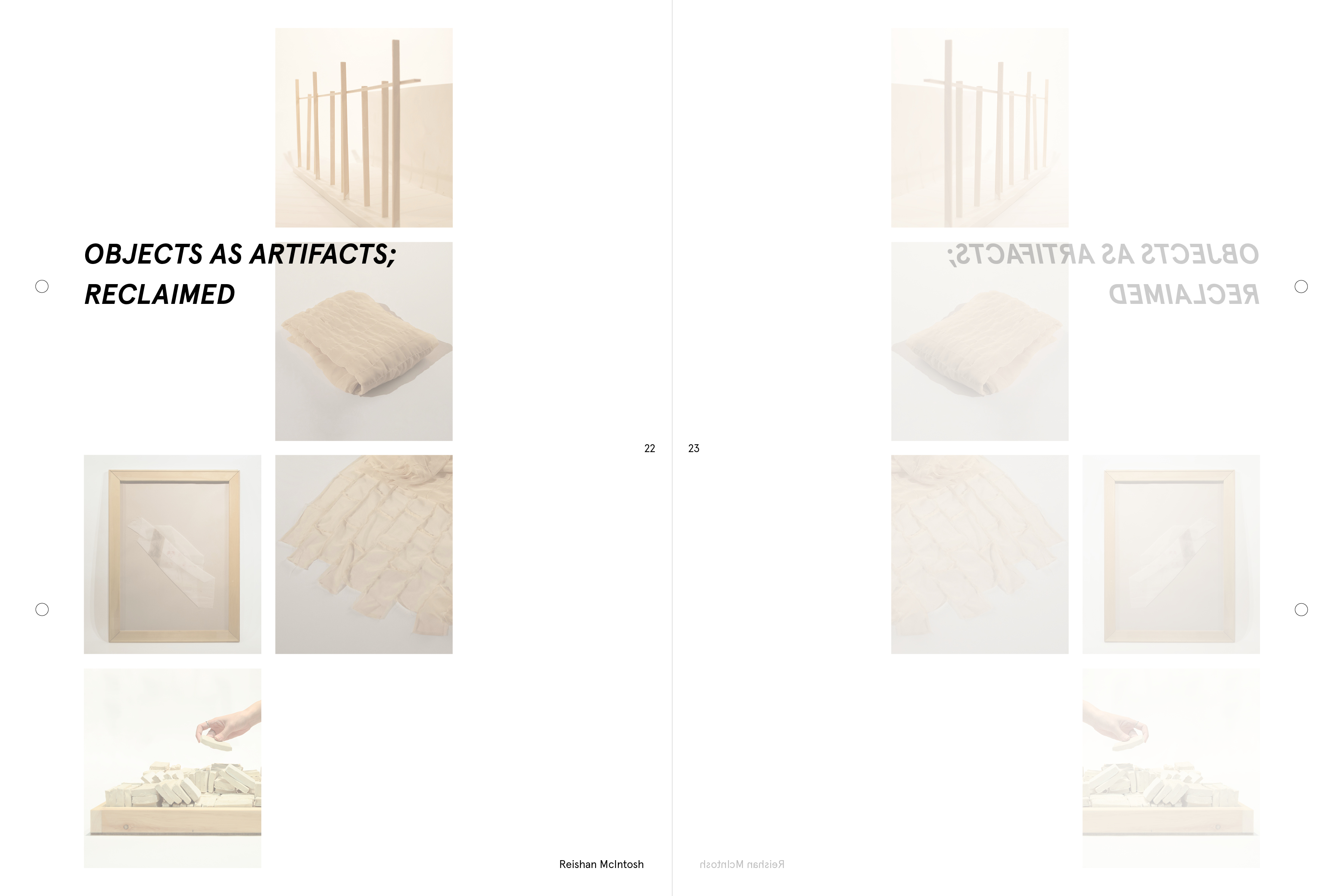

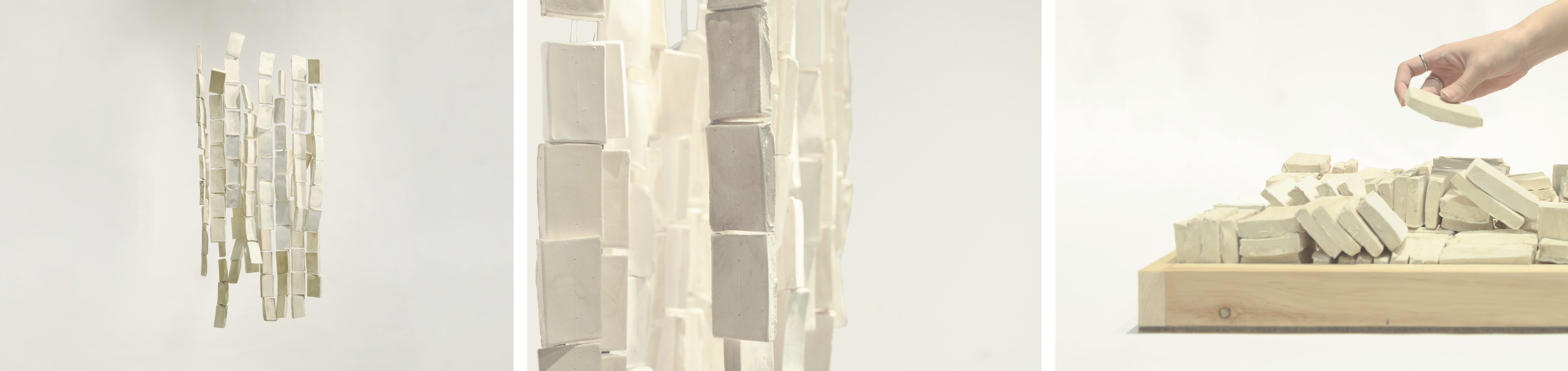

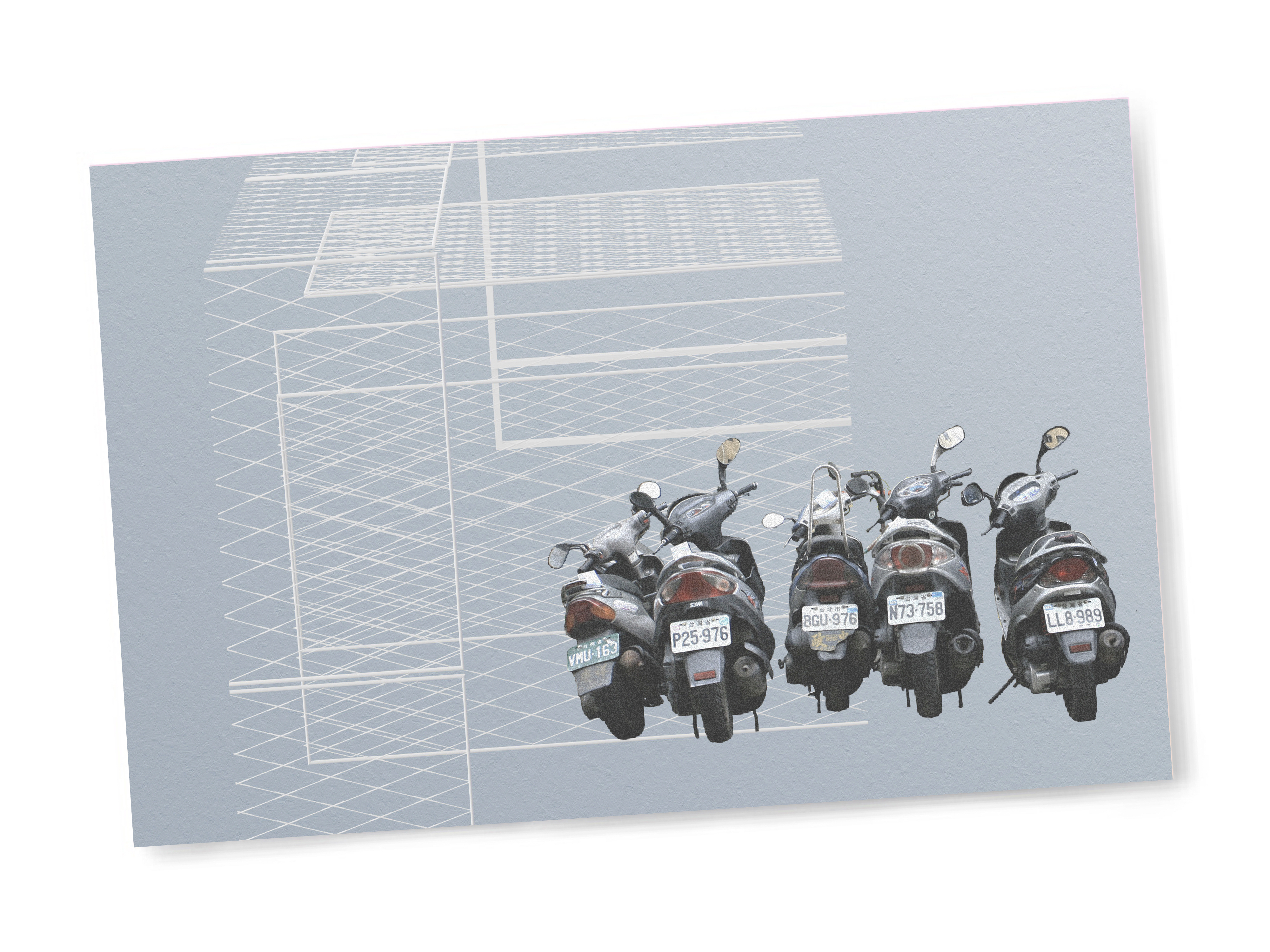

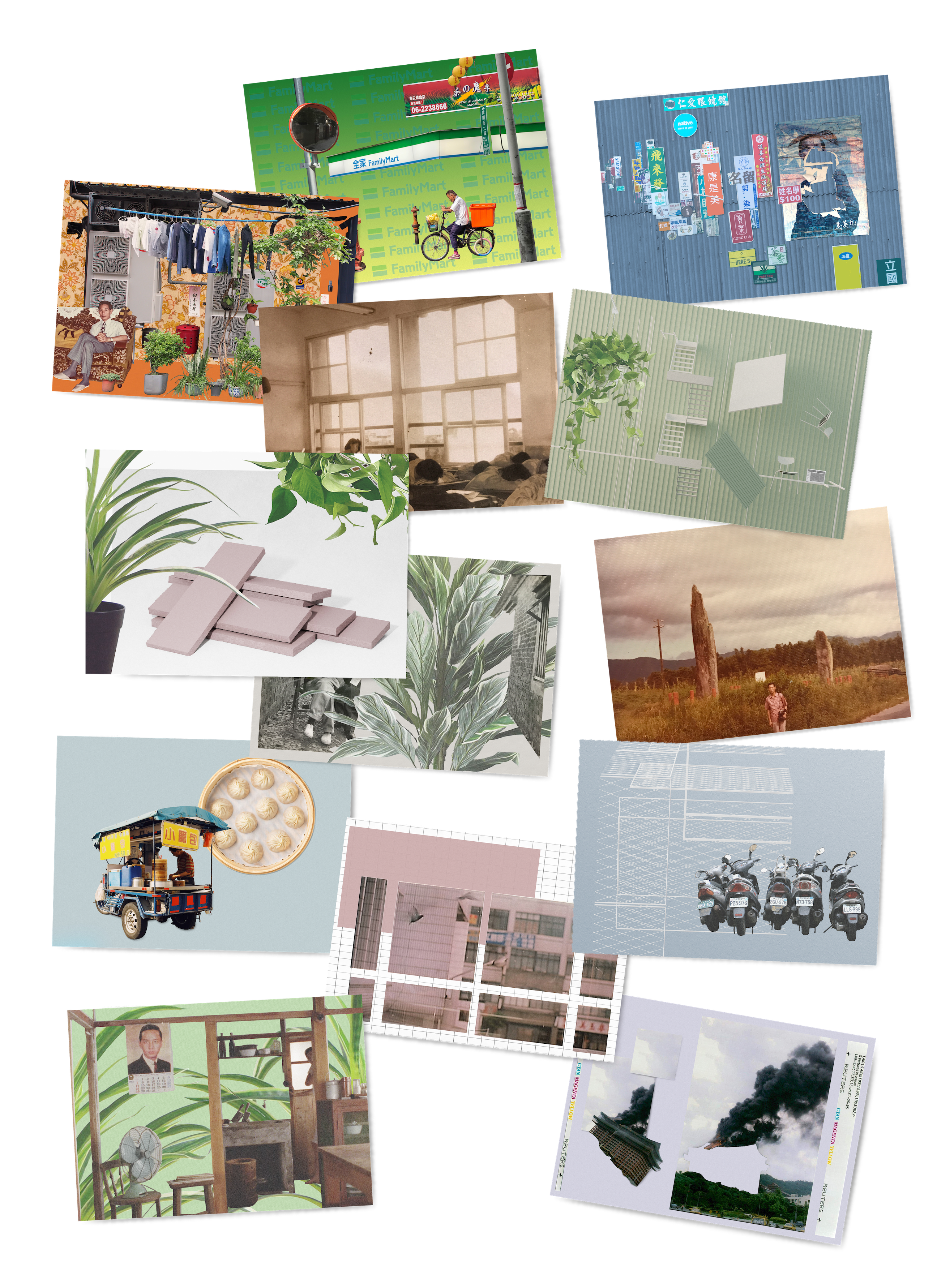

The process to analyze Taiwan’s in-between-ness came through a collection of artifacts. Working in another medium helped develop an intuition of the process by which unfamiliar, imposed materials and architectural elements were made familiar through user adaptation. In the example above, postcard images, with their own logic and narratives, were removed from their context and combined to form new spaces. Each postcard frames a moment with components of materiality, environment, and actions. they allow us to understand place not through monumental buildings or political agendas, but through the everyday.

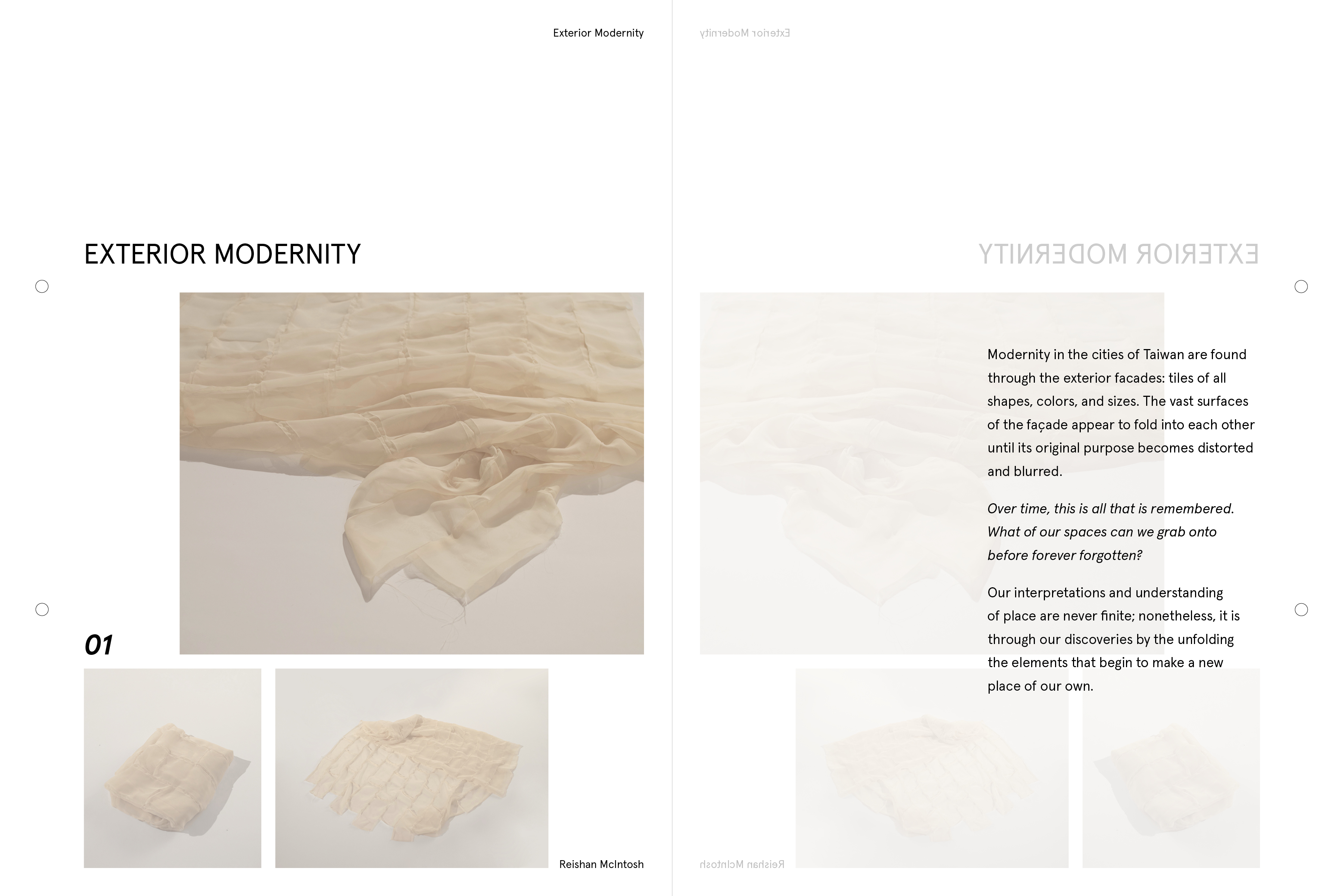

Exterior modernity: What of our spaces can we grab onto before forgotten?

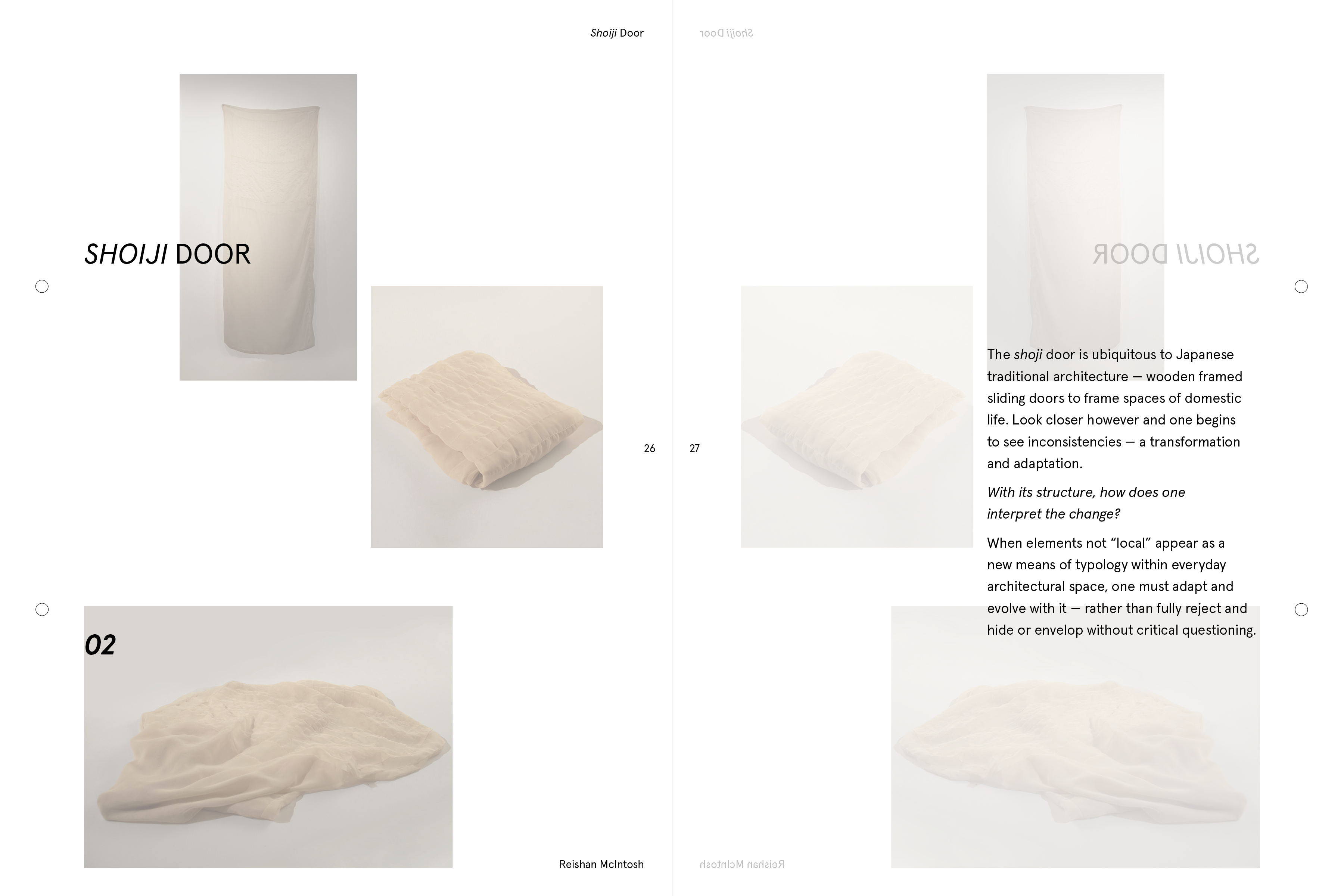

“Shoji“ door: Within its architectural elements, how does one interpret change?

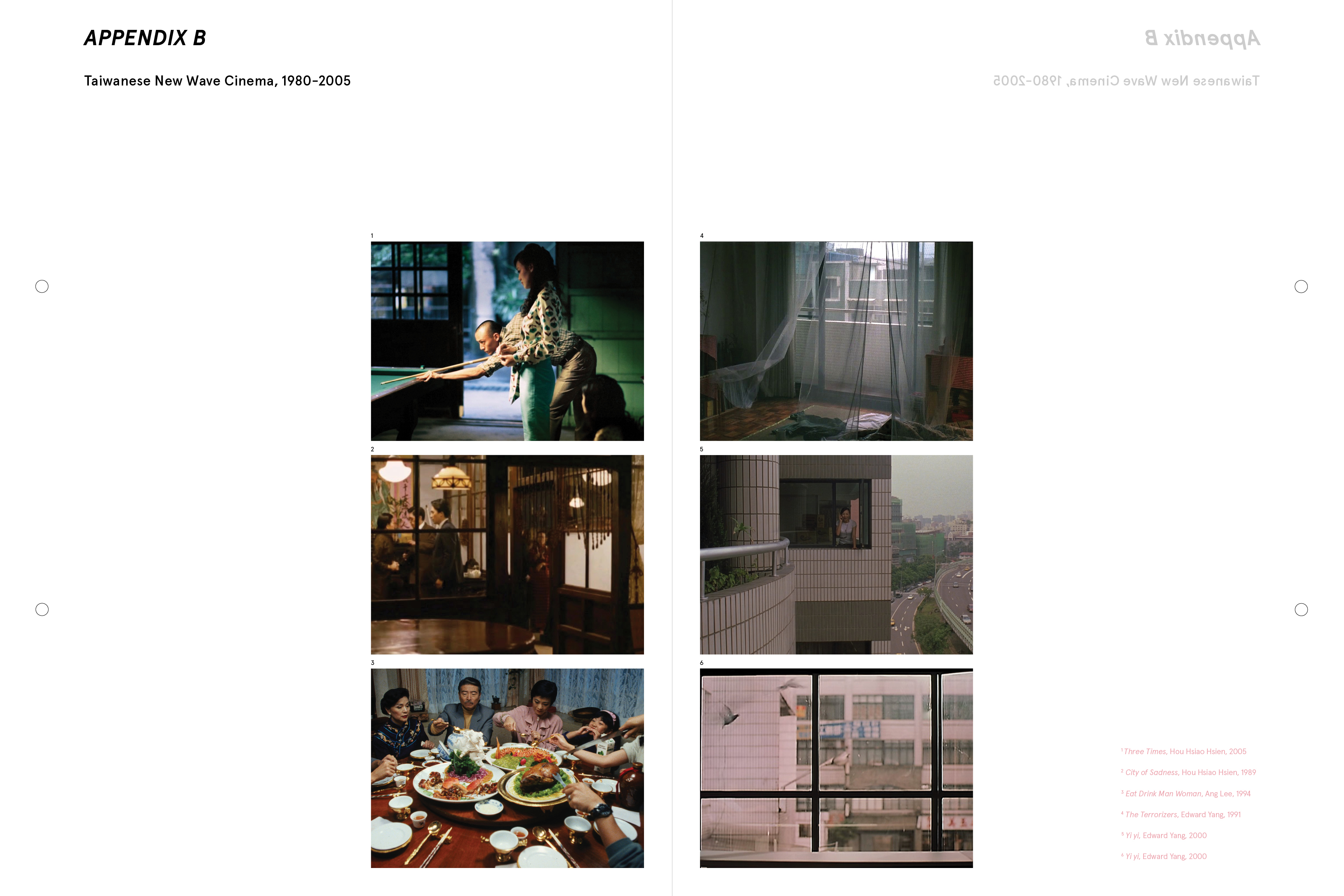

Washitsu (Japanese-style rooms) in Taipei from “A Brighter Summer Day” (Edward Yang, 1990)

Washitsu (Japanese-style rooms) in Taipei from “A Brighter Summer Day” (Edward Yang, 1990)

Hybridization of Japan-imposed architecture

Ornament as utility

Ornament as utility

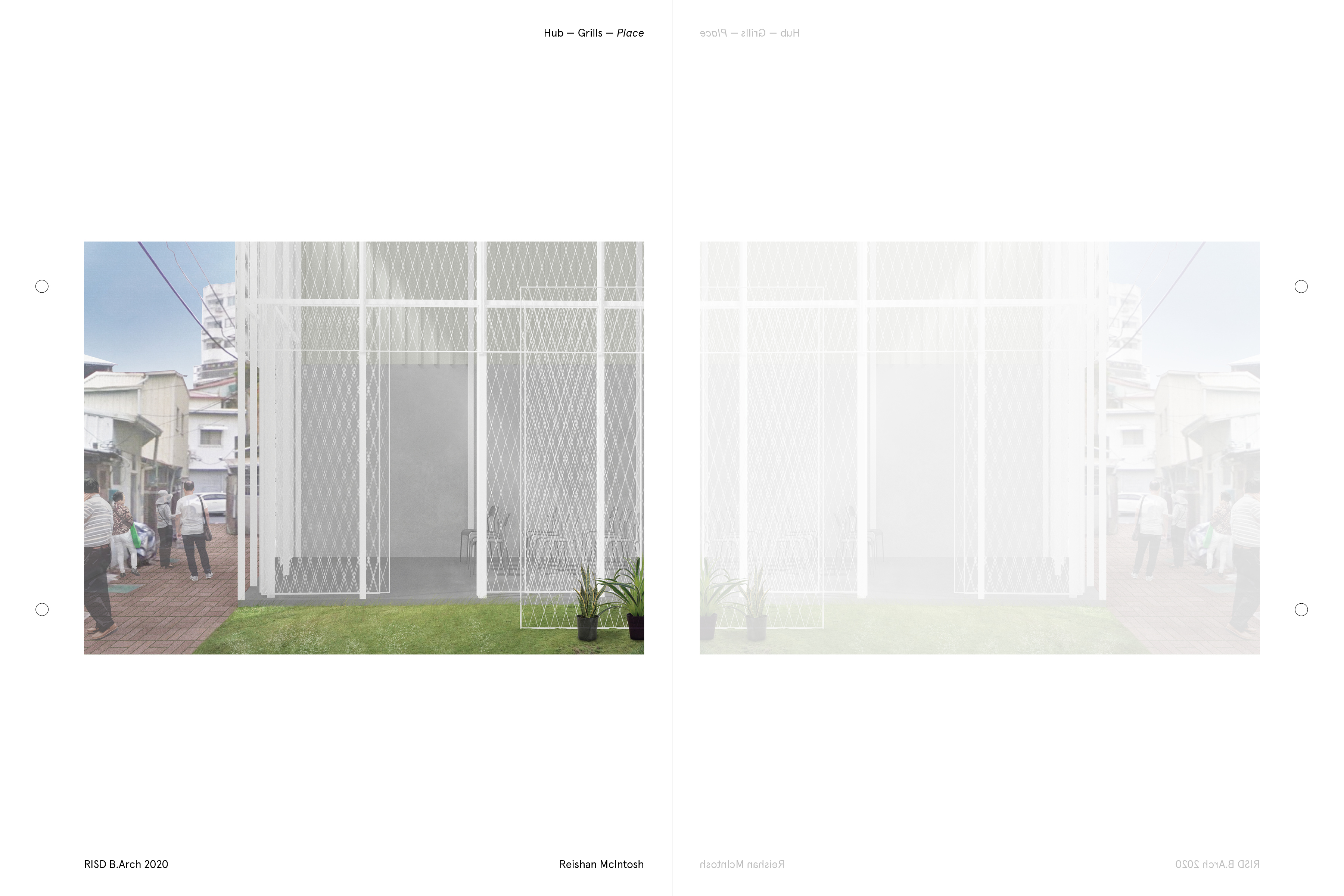

Boundaries are blurred: of city life, of cultural impositions, of space—citizens do a lot of sharing. If we consider the idea of mix-use and mis-use, sharing is a practiced habit. In Taiwan the gods, saints, and its citizens are all the same—temples share walls with apartments, an unassuming table with 7/11 snacks is placed in front of a business as an offering to the spirits.

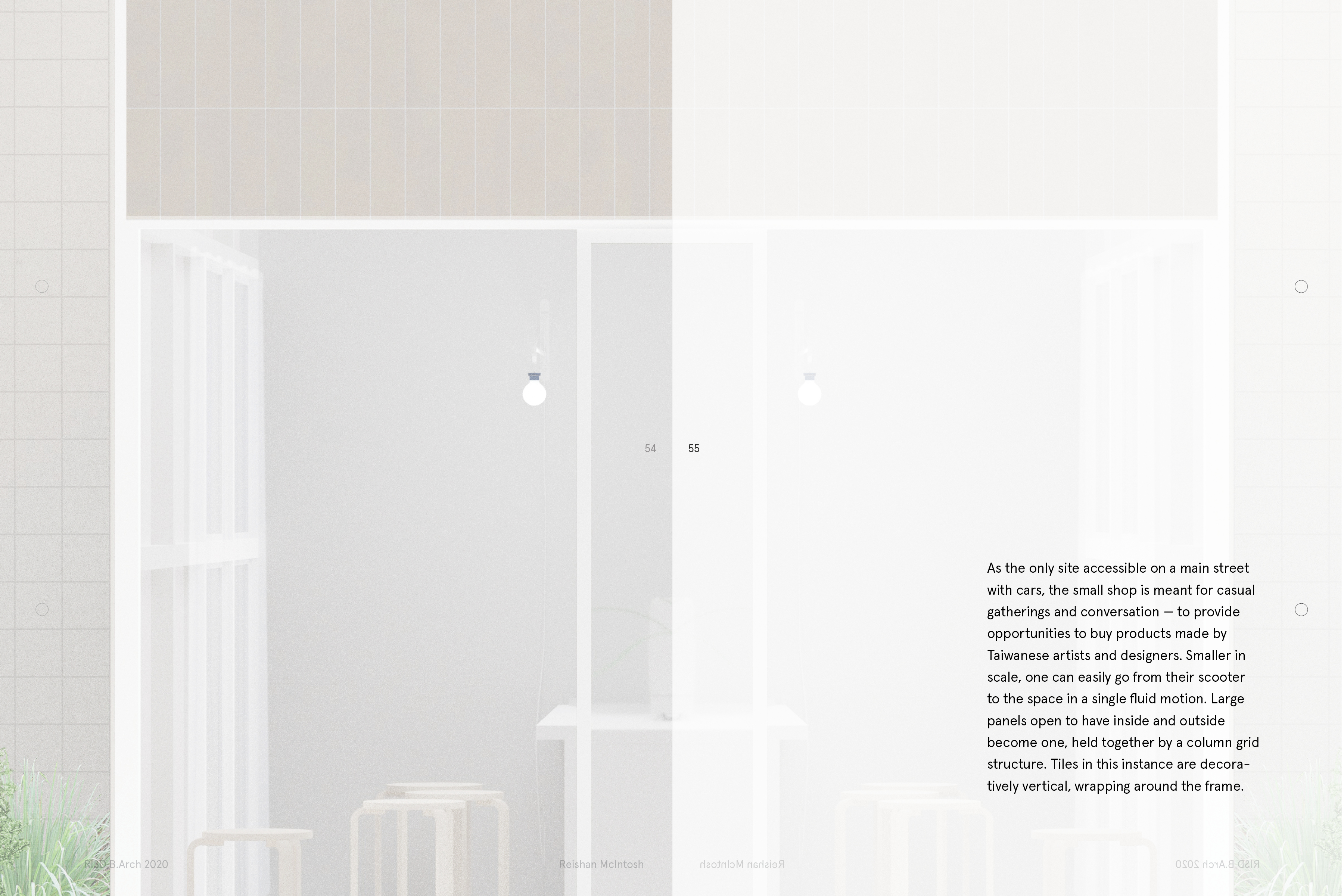

To place in context, the old capital, Tainan, is located far south on the island. Wide streets, implemented during colonial rule, are main arteries running through the city, but quickly, they divert to smaller streets, and then alleyways. While seemingly dense from above, the edges of the buildings don't mark an end, rather a series of thresholds where inside and outside fluctuate between one and the other.

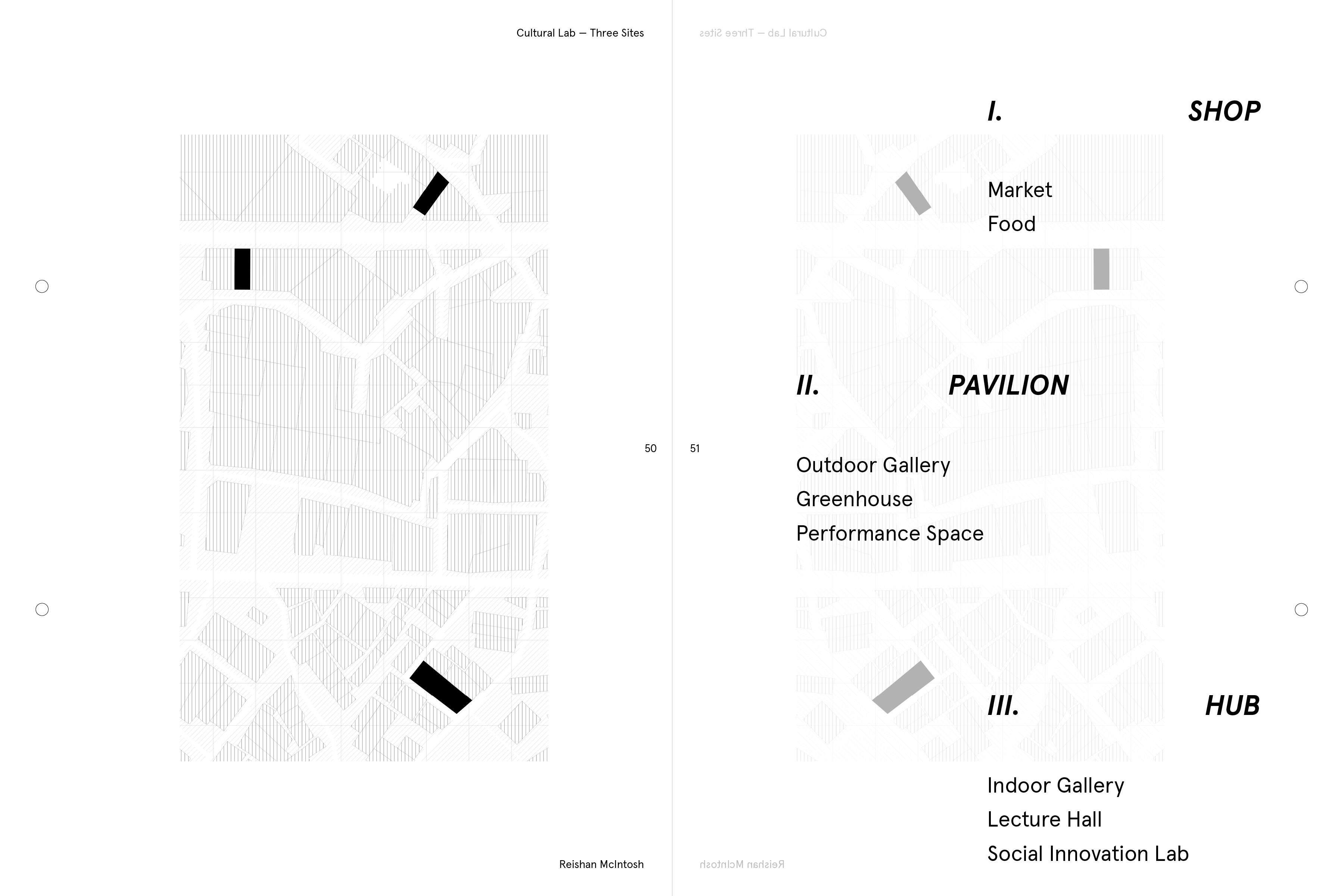

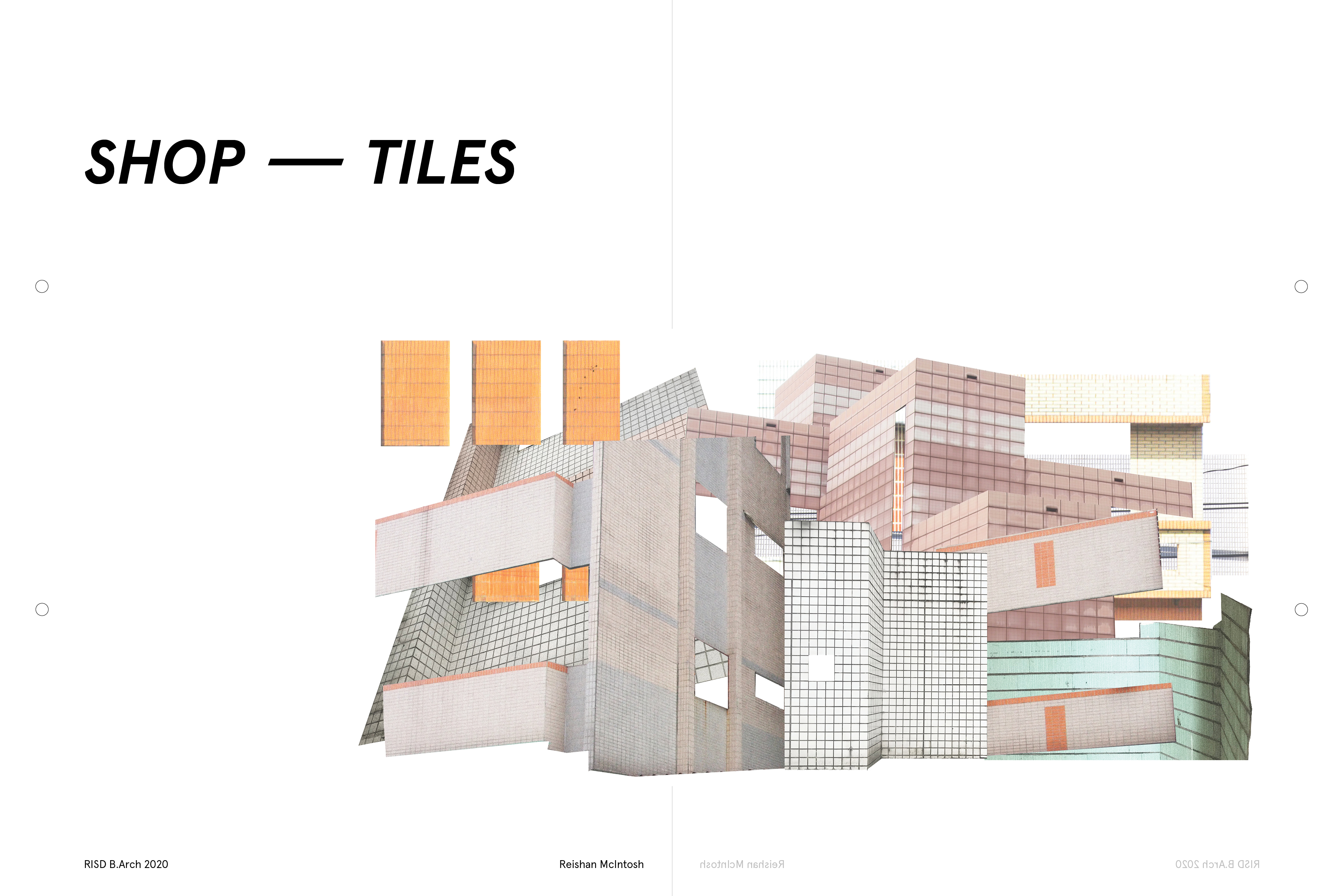

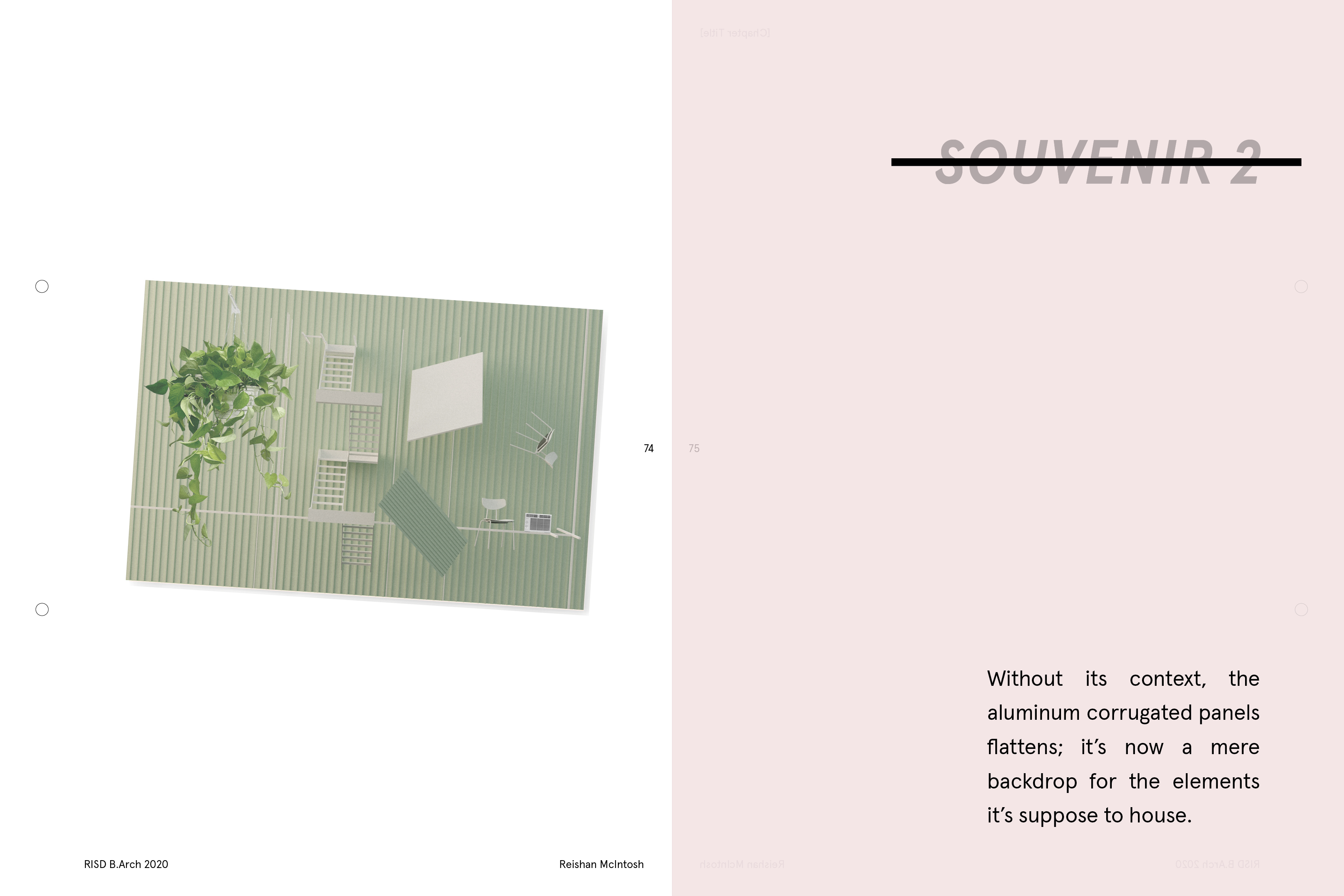

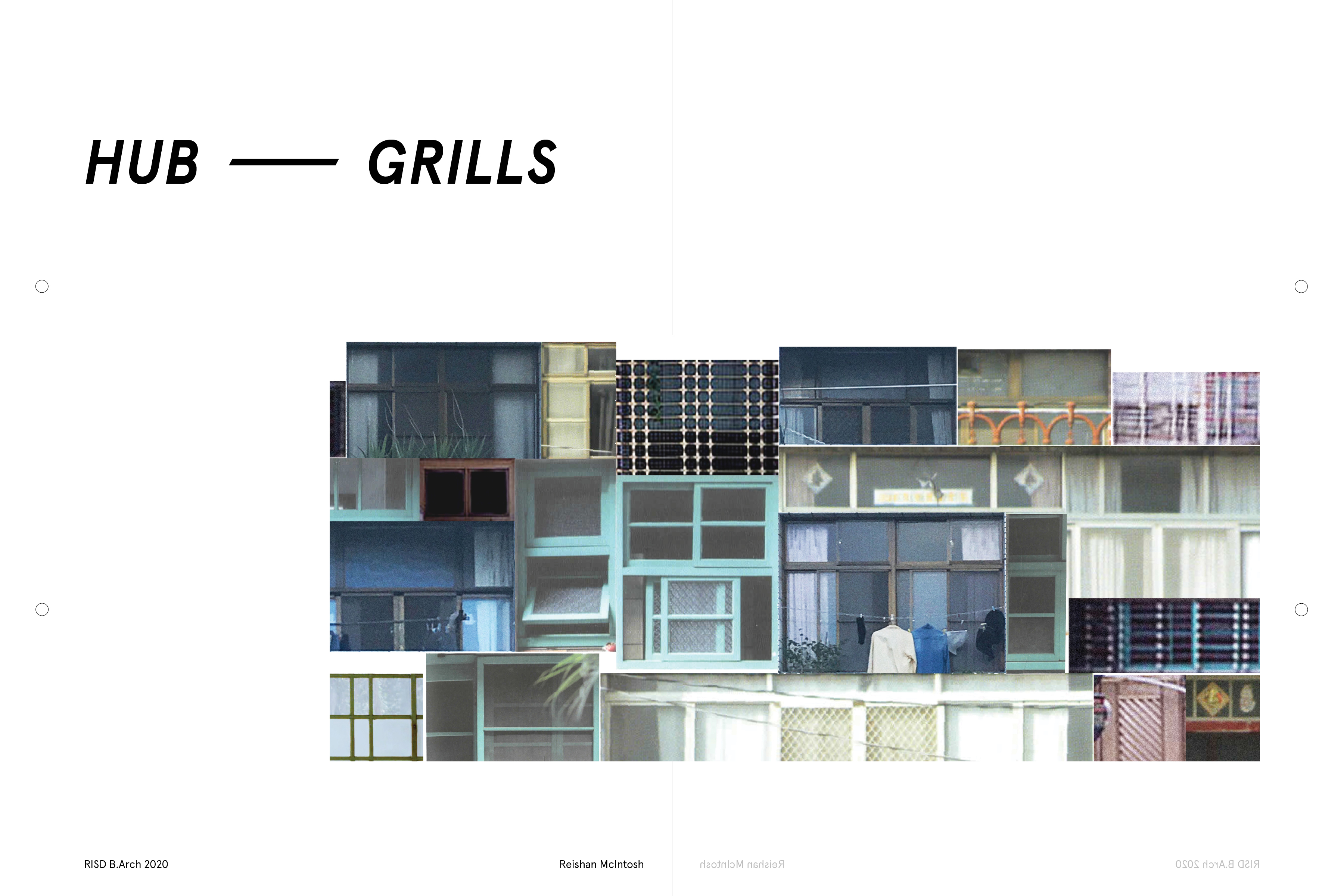

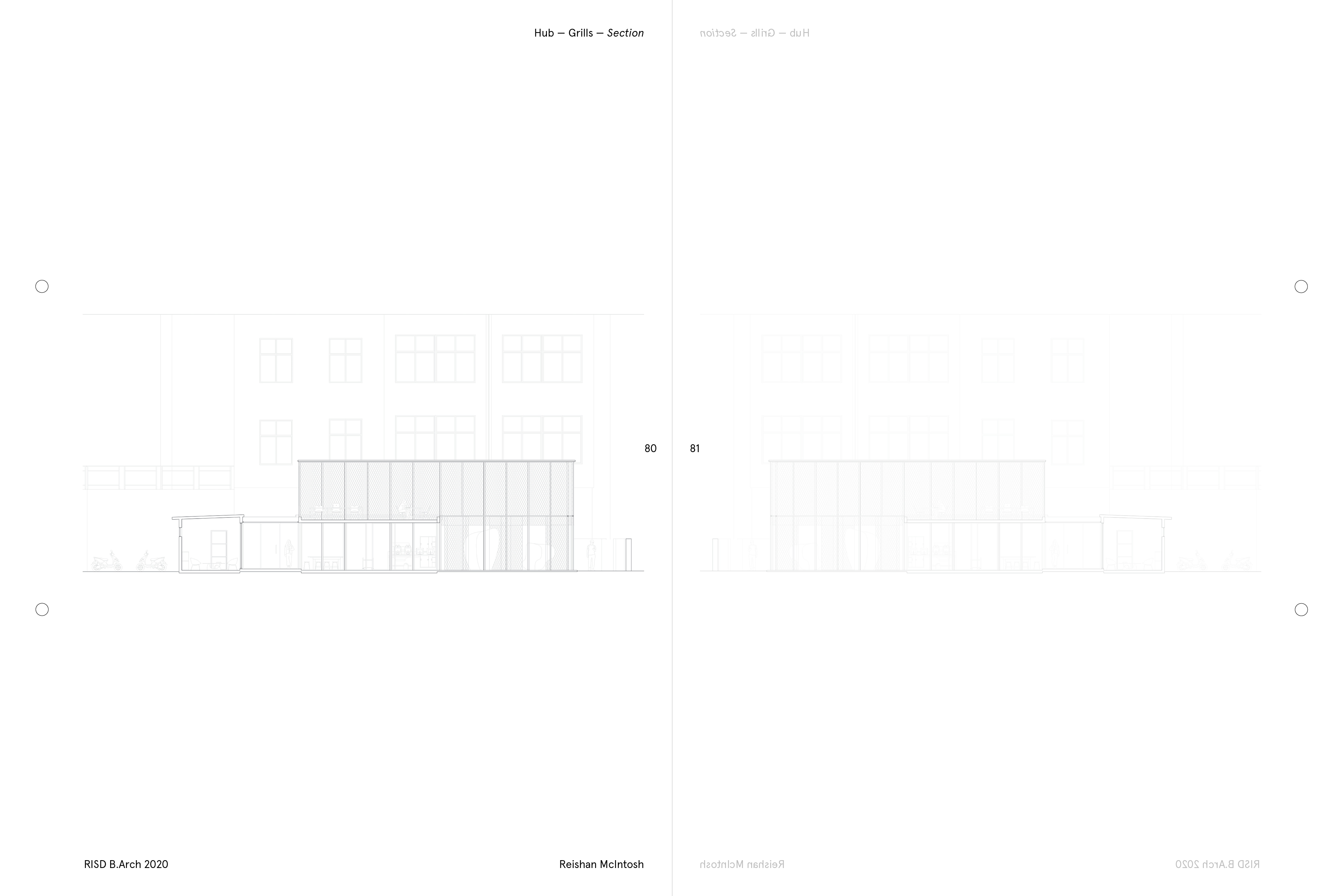

With each built project, comes an appropriation and exaggeration of material culture through two forms — the familiar (or the contextual) and the defamiliar (or the souvenir) — using corrugated aluminium sheeting, tiles, and window grills as examples. These dichotomies don’t necessarily need to become adversaries, rather they can be tools to both approach a place as an outsider and carve space out as a local.

Shop — Tiles

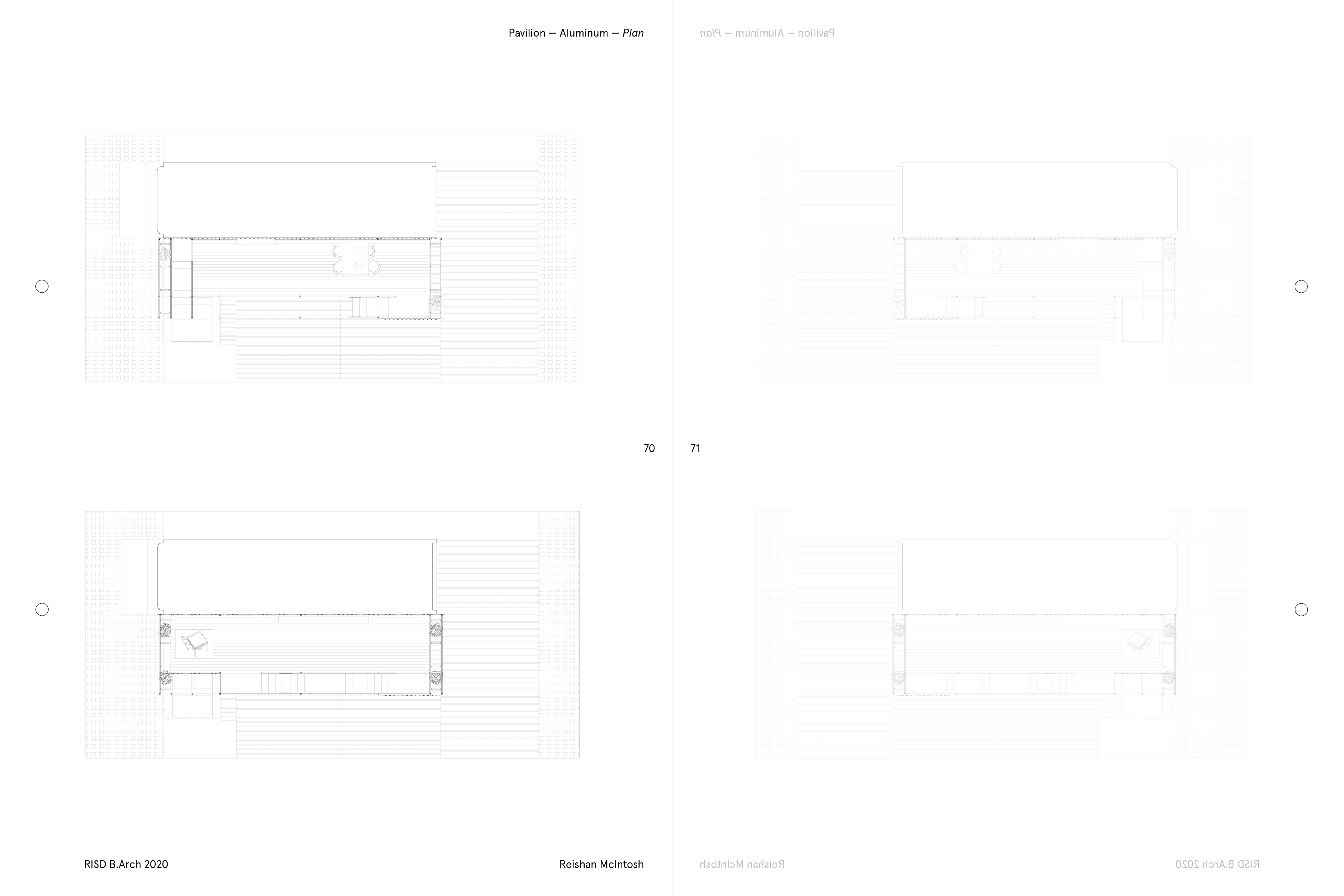

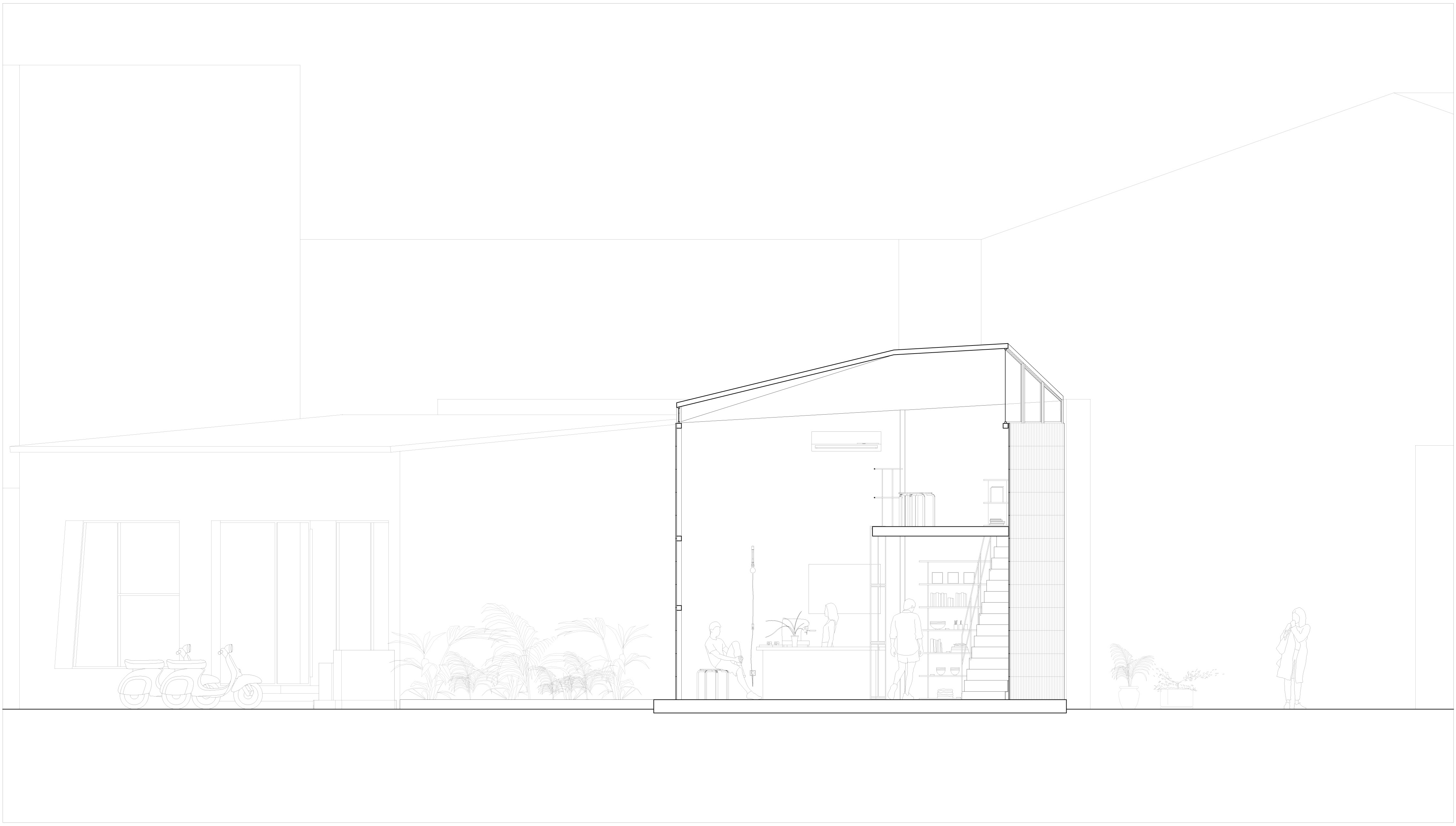

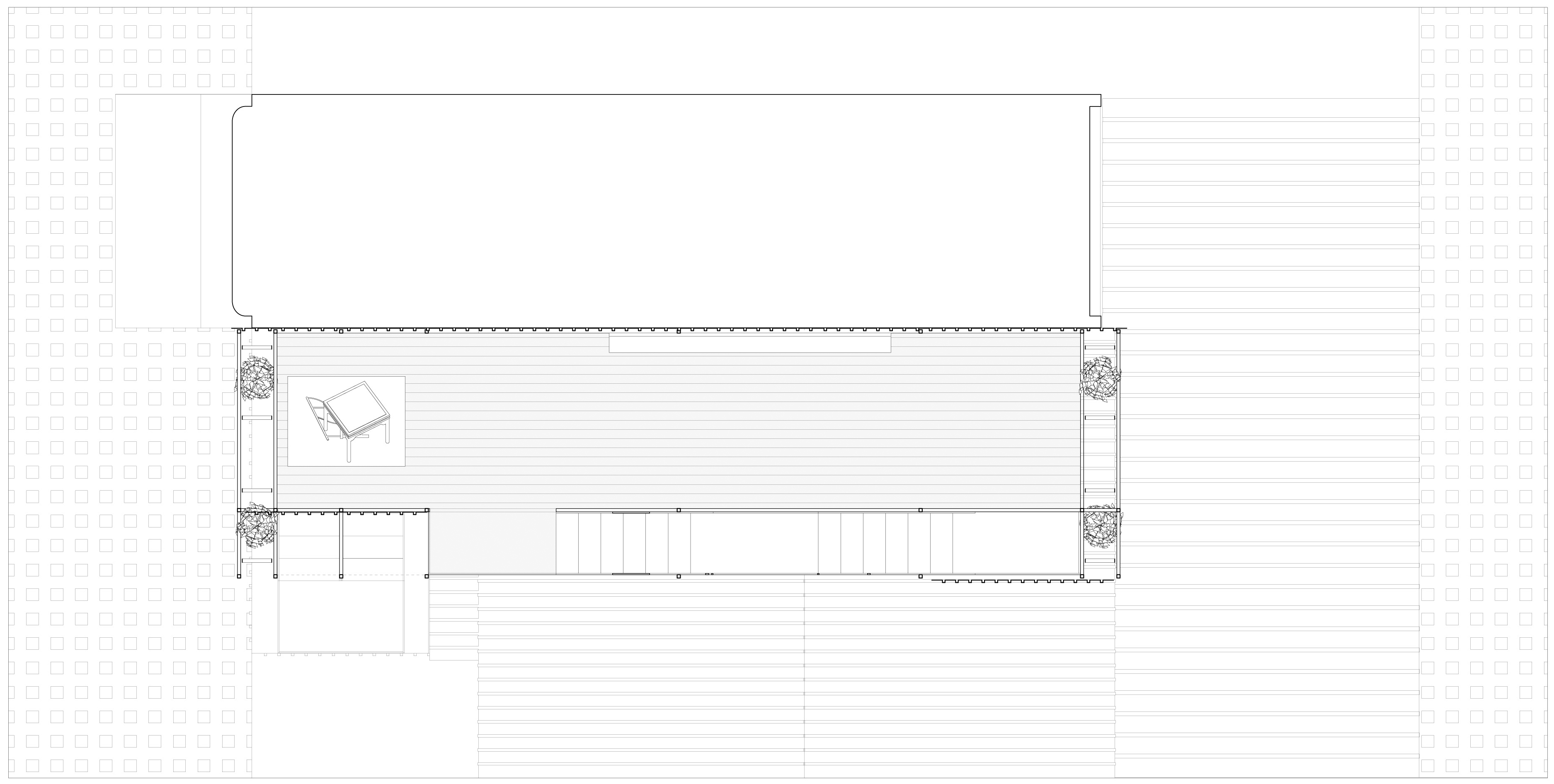

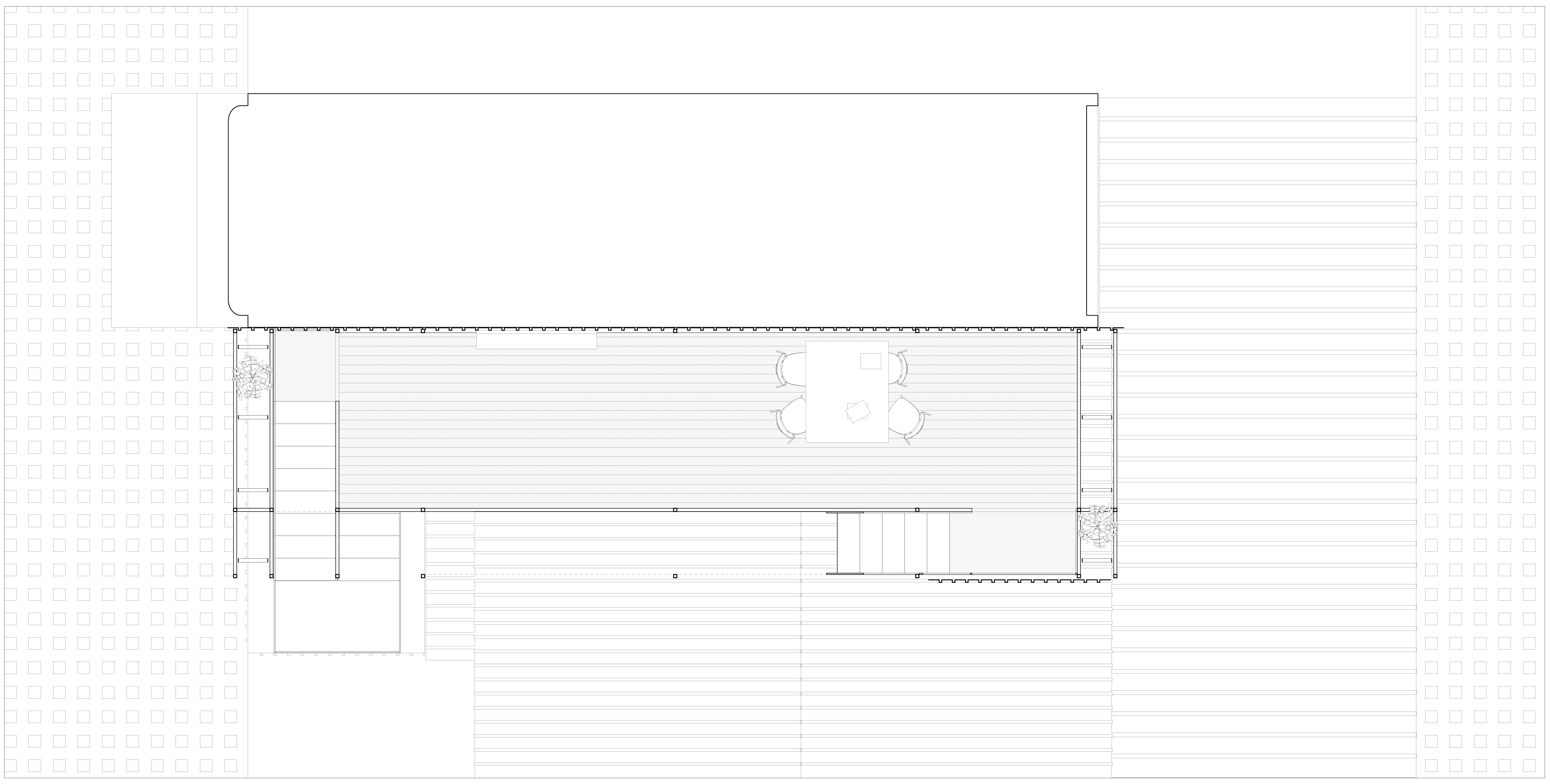

Pavilion — Aluminum

Hub — Grills

1 Foreigner at Home is part of an ongoing piece of work to guide my own practice. 2 Below is a collection of the work in digital book form. Please scroll through! ︎︎︎